labour-together-ge2019-review

System updates required: ground operations and digital technology

Common Knowledge’s submission to the Labour Together’s report on Labour in the 2019 General Election.

The other is In lieu of strategy: ground operations and organisational structure.

Contents

Understaffed development team, reliance on temporary staff

Hiring embargo on digital staff

Under-utilised digital technology volunteers

Staff contentions rather than collaboration

A lack of digital technology leadership

Siloed and manager-heavy organisation

Access to digital infrastructure

Usability of digital infrastructure

Gaps in the party’s digital ecosystem

Door knocking and issue mapping

A single view of voter contacts

Increasing accessibility to the party

Our report on the Labour Party’s digital technology comes amidst a general recognition that the party’s digital ecosystem is less than perfect, with consistent commentary about the unreliability of tools like Dialogue. The frustrations of many campaigners are linked to a lack of clarity about digital and data and how it is managed.

First we break down how Labour “does” digital from three aspects: data analysis for targeting purposes, digital social media, and digital tools for campaign organising.

Then we analyse the thematic issues and note their organisational dimensions.

We finally make recommendations about filling the gaps in the party’s digital ecosystem, including how the Labour Party as an organisation will likely need to adapt to make this possible.

How Labour does digital

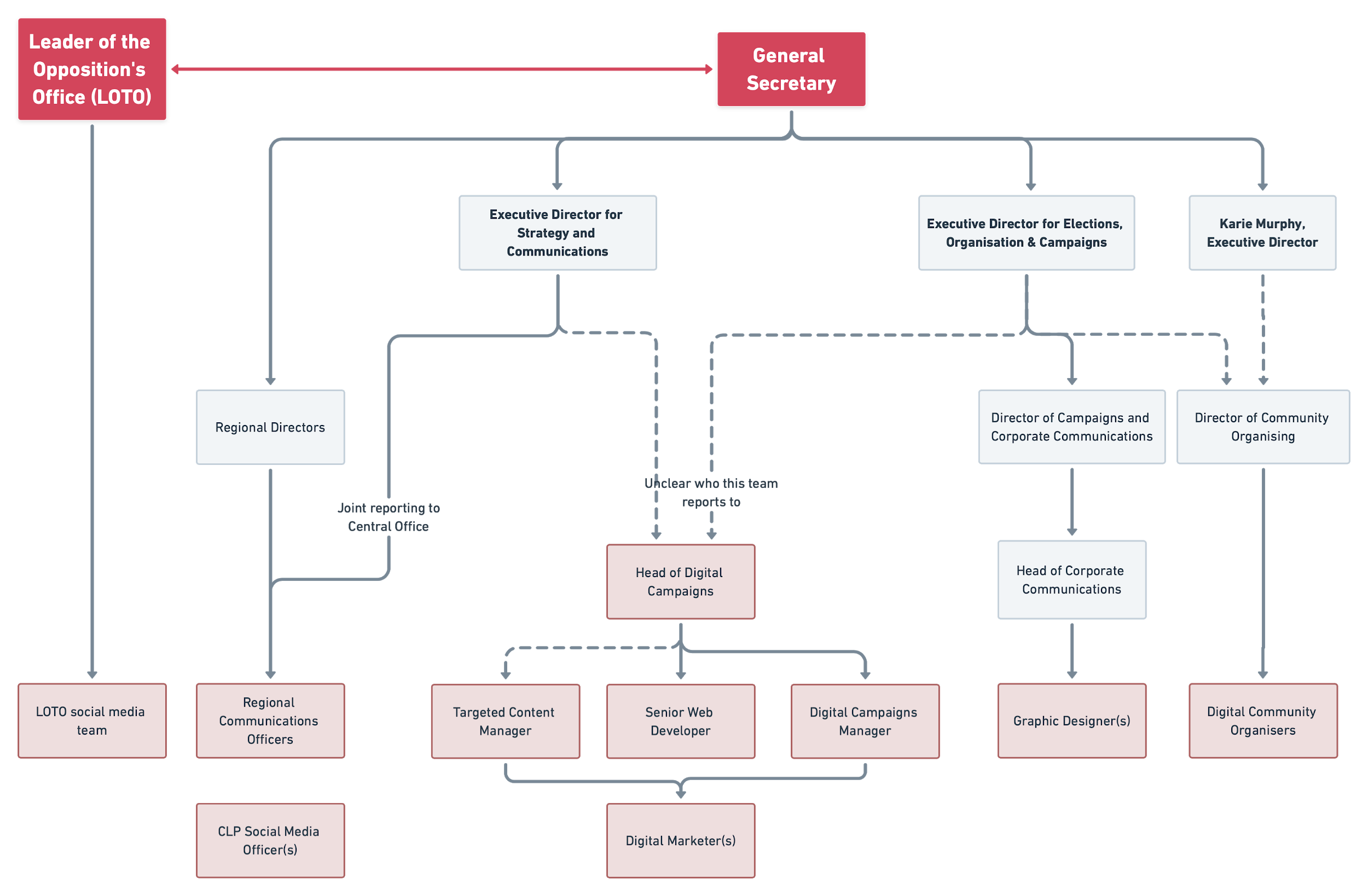

Talk about digital often conflates social media, apps and data but in the Labour Party a number of different hierarchies deal with these separately.

Social media

This was handled variously by constituency-level volunteers, regional office and COU staff as well as two national teams, one reporting to LOTO and the other (Digital Campaigns) reporting to, according to who you believe, the Executive Director for Strategy and Communications OR for Elections and Campaigns. Constituency and regional staff made extensive use of Promote.

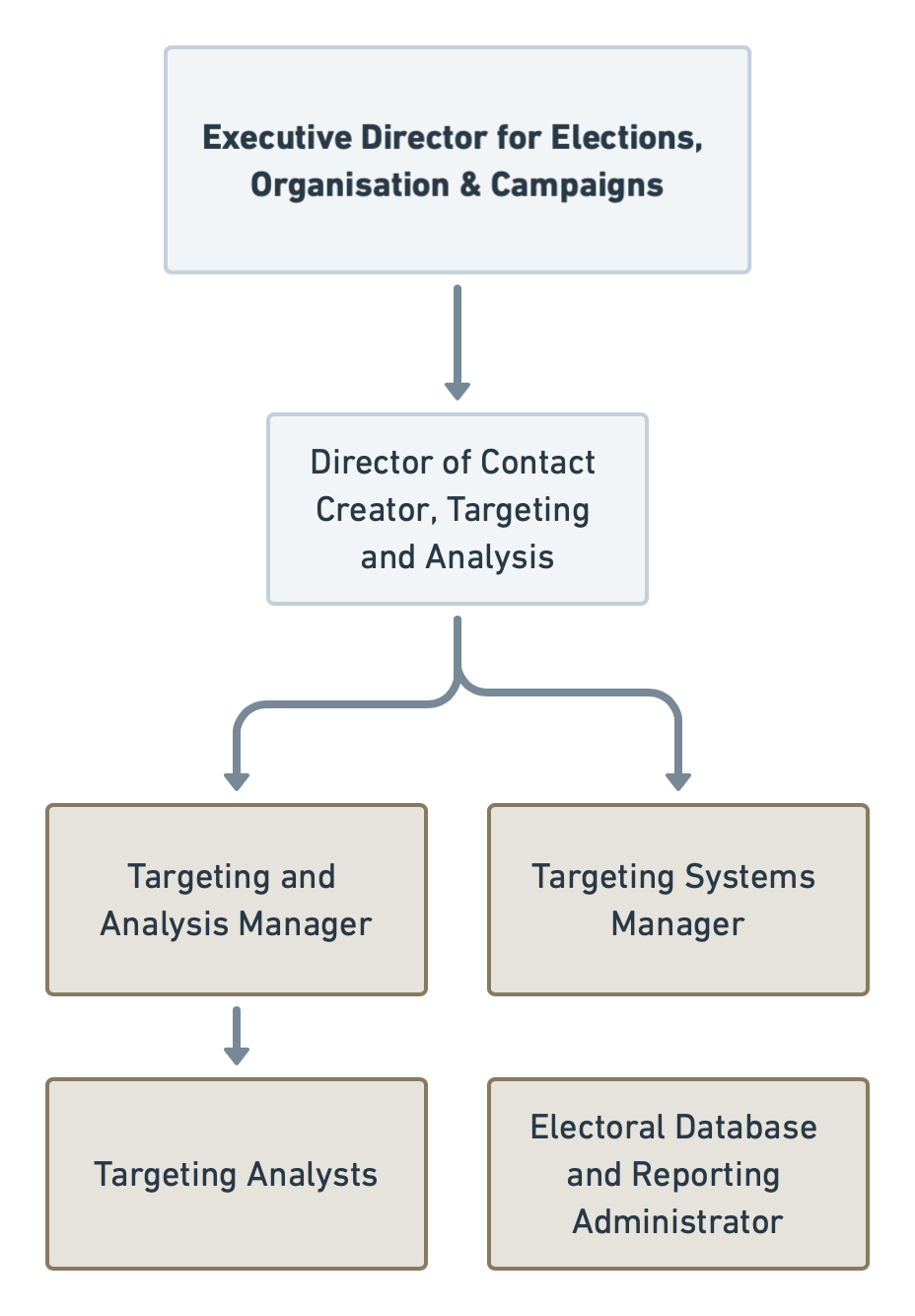

Electoral data

This was managed by the Targeting & Analysis Team, who produced models and recommendations like target seats, most likely voters, ideal contact times.

Target seats recommendations were discussed by the Strategy Group, a regular meeting of senior politicians, staff and advisors, and mediated by the regional directors in contact with constituency campaigns.

These recommendations significantly influenced NEC spending decisions for constituency campaign staff, who negotiated for organisers. As a last chance, constituency campaigns would go ‘cap in hand’ to trade union funding sources.

Ultimately, models from the Targeting & Analysis Team were fed through to the Insight digital tool which made recommendations to constituency campaigners as to who to target for door-knocking, phonebanking, social media ads and postal mail.

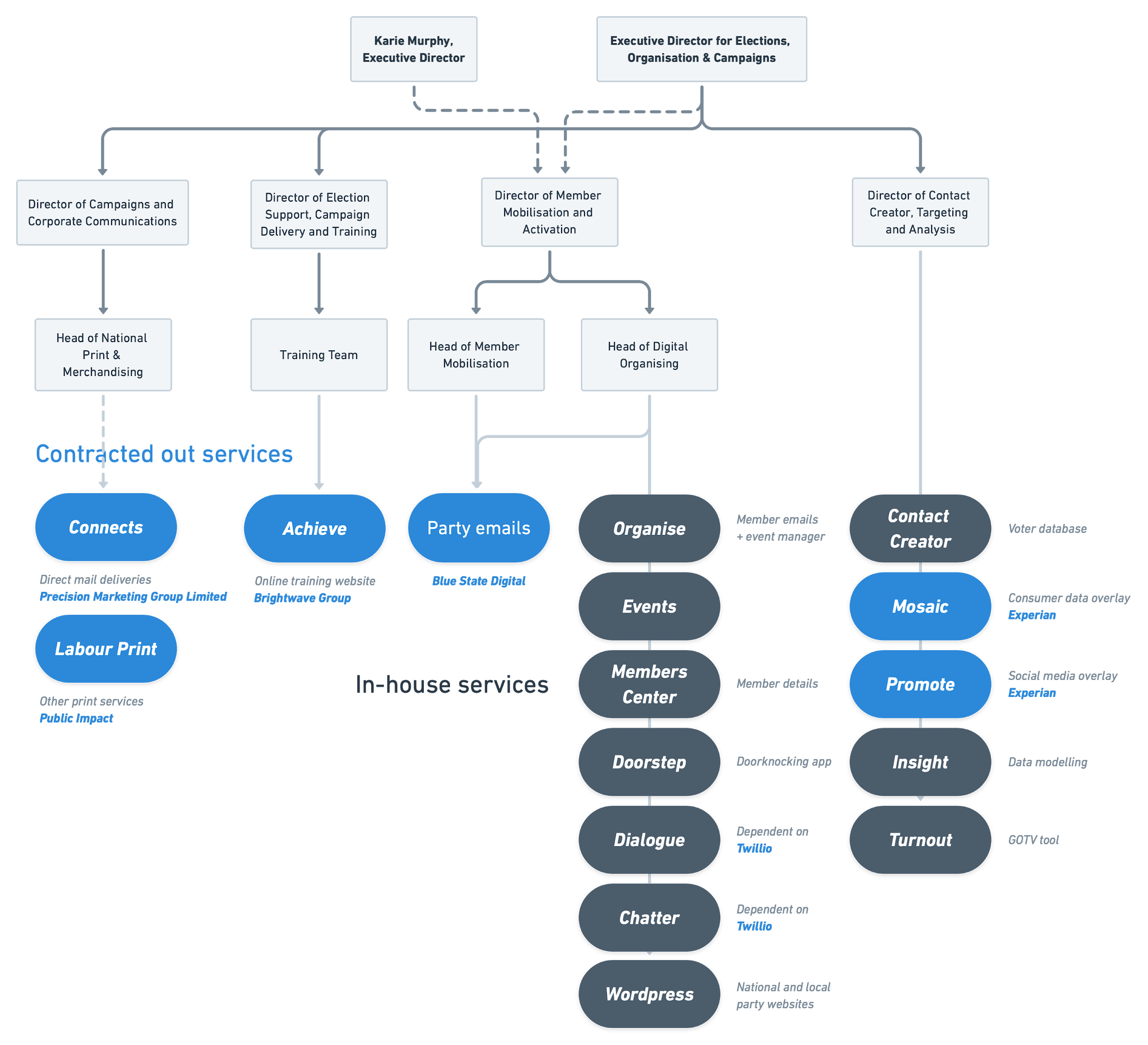

Digital tools for campaigning

These tools were used by constituency, regional and national staff and members throughout the campaign; this diagram points out the teams responsible for each tool’s maintenance:

What we want to point out is the sheer quantity of digital tools that the Labour Party operates, has purchased from third parties, and the spread of these tools across different teams and directorates.

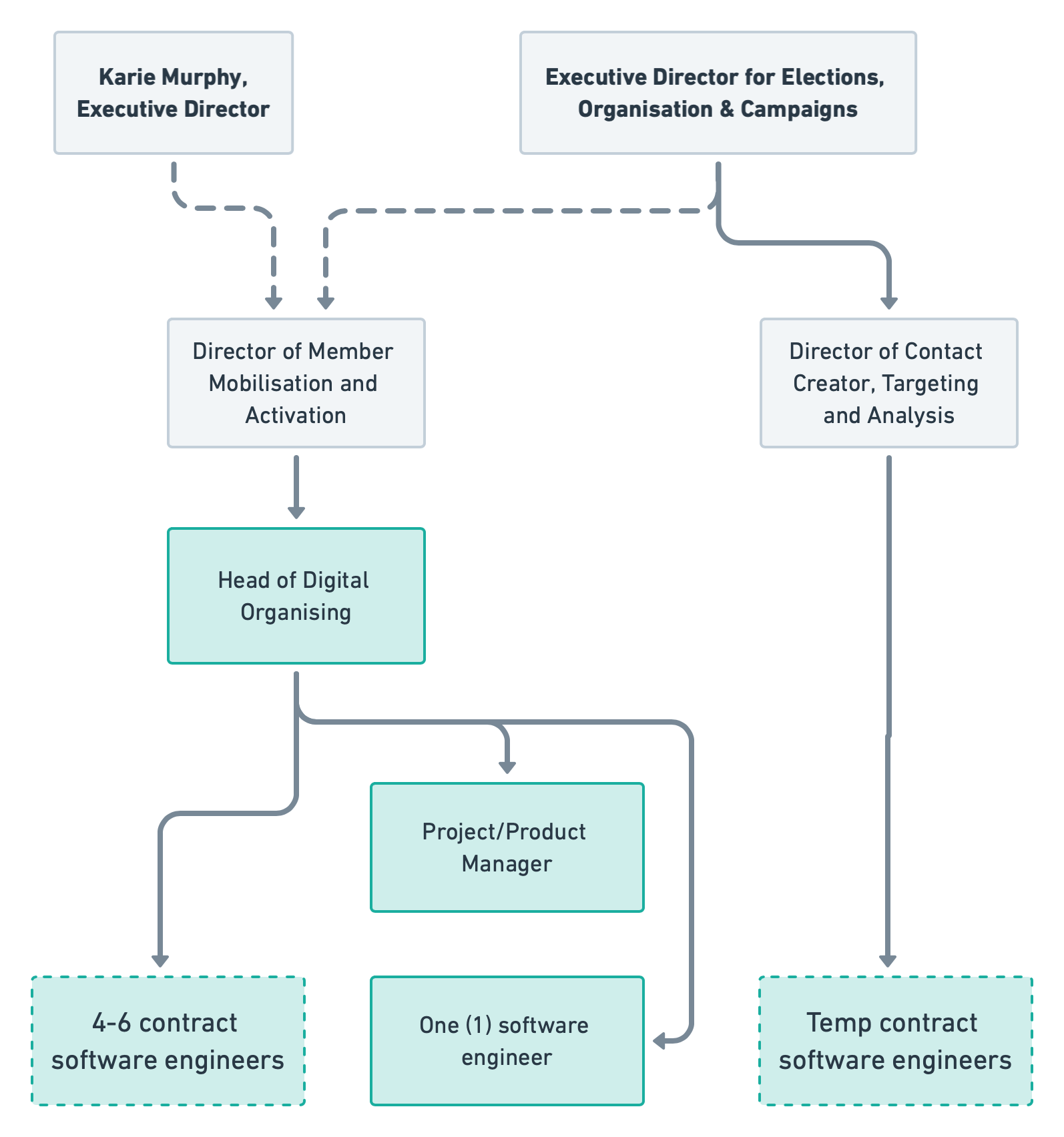

Frequently, comments about digital tools from members and staff will speak of an “Organise team”, a “Dialogue team” or similar. This myth needs to be expelled: the Labour Party has one full time software engineer dedicated to campaigning tools, responsible for 7 digital systems. The Digital Campaigns team also has at least one web developer, but they are not responsible for the vast array of tools described above.

Additional software engineers are brought in on an ad-hoc basis, such as during the election, or on a monthly retainer to build new features and handle issues of high usage and critical failures.

Understaffed development team, reliance on temporary staff

A lack of full-time development staff meant that a backlog of improvements, fixes and new features for tools like Dialogue, Organise and Events could not be implemented before the 2019 election actually began.

Throughout 2018 and 2019 a series of collective messages from CLP secretaries to the General Secretary and the “Organise team” were sent, noting with frustration the slow pace of development. Without a core staff to evolve the systems in tune with how they are used and experienced, these concerns have lingered on into election periods.

Our expectation for an organisation the size of the Labour Party would be to have one fully resourced cross-functional team working on digital tooling at all times. This would be around 7 +/- 3 people. The mix of skills which would depend on the goals of the team at a given time but, say, three-four software engineers, one UX and digital design specialist, and a product and project management specialist would be minimum.

A comparably sized permanent team can be found in most universities and larger charities. It should be noted that the commercial equivalents of each of these tools would resource whole teams onto each of them. A commercial equivalent of a tool like Organise would be Nationbuilder or even MailChimp, and they have multiple teams working on the product continuously. Universities and large charities are in a similar position, with multiple tools, but they also have permanently resourced teams, working on each tool in a serial fashion.

Hiring embargo on digital staff

A critical issue that faced the Digital Organising team and possibly other teams in Southside was a hiring embargo imposed by Finance & Operations.

Typically, in the months running up to a known or suspected election, temporary staff will be brought into teams as preparation. This is especially necessary in the case of the party’s software engineers for a few reasons:

-

The party’s digital systems are not fully documented as this takes substantial resources and is often deferred until after high-intensity periods like election campaigns.

Unfortunately, because there is only one full-time developer and contractors are only hired for the course of an election, new systems and changes to existing systems are often never documented. On the other hand, because systems are not documented, it takes more time to “onboard” a new engineer—i.e. familiarise them with the systems and development processes—before they can begin to be helpful. Knowing this was the case, Common Knowledge offered our skills in documenting and providing setup automations or instructions for each system in order to anticipate this situation and quoted for it. This was in August 2019. The proposal for this was blocked by the Director of Technology and this work did not go ahead.

This clear case of catch-22 has a knock-on effect: it increases the likelihood of introducing new bugs and decreasing reliability and makes fixing bugs less straightforward and self-explanatory. In light of the serious reliability issues faced by users in this election, this catch-22 is a serious cause for concern.

-

Onboarding a new engineer requires the time and attention of a team member. This is normally not a serious problem but the Labour Party’s Digital Organising team is responsible for seven live systems with only one full-time developer with support from the team head. When the hiring embargo was lifted at the start of the election campaign, the digital team staff were preoccupied with hiring and onboarding new staff which took their attention away from pressing work to be done on systems like Dialogue, which was deployed late and without adequate testing.

-

Because of the relative difficulty with hiring competent and correctly-skilled software engineers, a lead time of many weeks if not months is usually factored in for hires. In this case, the Digital Organising team was only at full capacity two weeks into the six week campaign.

Especially given the need for inter-constituency campaigning and the resulting need across the party for Dialogue, this case seems to be a straightforward failure of consequence management at the highest levels: financial restrictions affected the development of basic campaigning infrastructure, which likely affected the election result.

It should be noted that in 2017 as in 2019 foundational development tasks were being done during the election, such as the implementation of the Login For Labour internal authentication system.

Under-utilised digital technology volunteers

Labour is fortunate enough to have several networks of member volunteers who are technology professionals. Overall though, technical volunteers were an under organised and underutilized resource in the 2019 campaign. This represents a major missed opportunity.

Coders for Labour[1] (formerly Coders for Corbyn) is a fairly dead network of technical volunteers. During the campaign Coders for Labour updated their Labour tax calculator produced in 2017, built a tool for examining leaked trade documents[2] and updated fun Labour shareable sites[3]. But the level of activity was lower in 2019 compared to 2017.

Momentum has their Momentum Tech Network. This is also under utilised, as Momentum has not yet substantially dedicated resources to it. Within the campaign, Momentum bootstrapped the Momentum Tech Collective, a new initiative from this wider network which on GitLab has 50 members. Some of this was used well, some poorly. Full time volunteers, “super volunteers” took up substantial roles coding for the team and contributed a great deal. But the vast majority of volunteers remained unorganised and their level of organisation became lesser as the campaign wore on and staffers and even super volunteers became more busy. Contributions from the Momentum Tech Collective were often left unmerged because of lack of time to complete code review. This is despite the fact the core Momentum team deliberately made technical choices that would allow for easy volunteer onboarding and allow contributions to be made.

Campaign Lab[4] is a more substantially organised network of volunteers, with a more data science focus, based around monthly meetups. This is because unlike other networks it has two people from Labour Together actively organise it and it has regular meetups outside of campaign time. During the General Election, one Campaign Lab volunteer produced a substantial Get Out The Vote dashboard[5], which closely followed existing Labour practice and carefully augmented it. This was used in a number of CLPs for their activity on polling day. However, it was not taken up by either Labour or Momentum for wider distribution in part because it was felt it required rigorous testing before it could be officially distributed.

During the 2017 election campaign, technical volunteers were encouraged to get involved at Labour HQ. Labour HQ was open to technical volunteers at all times to work on projects for the party or their own projects to contribute to the campaign which, if sufficiently on message, could be absorbed by it and made official. These technical volunteers produced substantial pieces of campaign infrastructure in collaboration with Labour staff like the first public version of Labour’s mass text messaging tool Chatter.

This did not occur in the 2019 as it was felt managing volunteers was excessively burdensome. The party neither embraced volunteers and outside technical help at the expense of volunteer management, nor defaulted to a suitably resourced ‘in-house’ approach with the expense of hiring long-term contractors.

One serious issue for all technical volunteers is a lack of access to core Labour Party tools. As noted, there a substantial section of the membership from the digital technology community that supports and campaigns for the Labour Party, but:

-

They are not able to contribute towards the party’s infrastructure, such as fixing bugs, adding simple improvements of usability, or optionally new features, because the code is closed to the public and there is no technical documentation.

-

Nor do they have access to sufficient data to provide analysis and insight, despite a large data science capacity within the Campaign Lab community.

-

Finally, there is a lack of clarity over the party’s digital (and campaigning) strategy that hinders coordinated action by party activists.

Both Labour and Momentum did development in closed repositories on GitHub and GitLab respectively. There is also long debate over whether proprietary political technologies should be open sourced which is strongly tied to the concern that they will then be open to exploitation by ‘hackers’ or stolen for use by ‘the other side’.

To these points our recommendations are to take a pragmatic and staged approach to open development:

-

A phased rollout to additional volunteers, supported by an increased staff, can seek to document and close off critical bugs, with a defined pathway to full open source.

-

Orienting the party’s digital tools towards its unique capacity to organise a mass membership will mean that the “system” is not just reliant on smart software, but will also require the same social base. You cannot download people, after all. Tools will be useless for other organisations without these numbers of people. We note that Dominic Cummings has open sourced the Brexit campaign’s digital platform.[6]

Staff contentions rather than collaboration

At some point it was mooted to hire regional digital officers who could facilitate wider and more effective use of existing tooling — a prominent concern of some staff. In one version of events, these resources were instead diverted to other digital staff roles instead.

On the other hand, many members and staff from teams that received those new digital staff have reported frustrations about basic reliability (for example, the late development of Dialogue hindering campaigning) and at the party at large for not commiting to a digital strategy which enables new forms of organising.

There is a basic interlocking frustration between staff and members around tech availability on the one hand and capacity availability on the other. This looks like product of a lack of shared understanding around the resource allocation and budgeting decision of their mutual wider department, producing what seems to be an unproductive relationship.**

**It would be expected that different staff teams work together productively, rather being divided and put into tension against one another. Indeed we would advocate digital staff (software engineers or UX designers) being permanent members of other teams like the regional offices, COU, Digital Campaigns.

Making improvements for campaigners requires an ongoing appreciation for the scale and distribution of challenges facing them. Without this understanding, organisational tensions build up.

A lack of digital technology leadership

In 2015, Tom Watson led a digital transformation initiative through the then ‘Digital’ team, from which Digital Campaigns and Digital Organising were later spun off. The intention was to cohere the party’s tools and infrastructure and ensure they were servicing campaigners in the best way possible, devoid of archaic processes and critical issues.

Staff familiar with the project noted that this effort lacked buy-in from the various Head and Director-level managers of the party (of which there are many). The challenges of working in this environment were compounded by the highly factionalised and contentious atmosphere that has continued to present.

It felt like being a bull in the china shop but the china is invisible.

— An interviewee familiar with the digital transformation project

Despite six months of work, staff noted they had not once been able to gain access to key tools like Contact Creator despite direct requests to relevant director level managers. The office dynamics led to despair and resignations.

The Digital Team function was then replaced with an outsourced provider to create a corporate plan, although they had no campaigning or political experience. This ‘technology strategy’ was then adopted under then-General Secretary Iain McNichol but not shared with any staff actually involved, likely in part because it was “incendiary”: it proposed a centralised function across all technical systems which contravenes the division of technical ownership between the Digital Organising team, Contact Creator team, Head of Technology.

While we believe that some clarification of team structure and their roles and responsibilities is important (though tending toward expansion not contraction), modern digital teams are not a centralised function of organisations where digital work is important (the siloed “digital department”), but rather are embedded in different functions working in cross-functional teams.

This strategy document’s production resulted in the appointment of a Director of Technology, who was described as “totally ill-suited to the role” by staff we spoke to. “This was apparent to most people outside of senior management within weeks but it took two years for him to go.” The Director of Technology left their post during the 2019 election campaign.

During their tenure there were two wider roles: a programme manager and a ‘configuration officer’ and an intention to manage a development function, but this did not come to fruition.

There was a technical leadership vacuum at a time when technical investment seemed to be tightly scrutinised, the technical capacities of the party are stretched fragmented, and there are many systems to maintain and improve, aside from many demands not met by digital technology.

The lack of technical leadership (oversight, analysis, coordination, advocacy) has left key infrastructure vulnerable to failure and prevented training, improvements and innovations that, together, would have almost certainly improved the election result.

Digital leadership comes from managers actually committing to digital transformation in the whole organisation, not as “directors of technology” or somesuch.

Empirical research on digital transformation across several thousand organisations of various kinds has identified general “cultural and behavioral challenges” as the most prominent hurdle to successful digital transformation projects, a wide margin ahead of issues of pre-existing digital infrastructure or attitudes towards technology per se.

NCVO similarly noted that in 2020 social purpose organisations will likely need to “review their organisational culture, including attitudes to risk and innovation”[7] in order to benefit from digital technology. The McKinsey report identified “three digital-culture deficiencies: functional and departmental silos, a fear of taking risks, and difficulty forming and acting on a single view of the customer.” [8]

But cultural change is more difficult in older corporate forms of organisation that rely heavily on isolated teams and steep management hierarchies.

Siloed and manager-heavy organisation

Organisational theory would suggest that good work gets done when a level of autonomy, mastery and a big cause to rally around is present.[9] This is sadly not the prevailing culture and mode of the Labour Party.

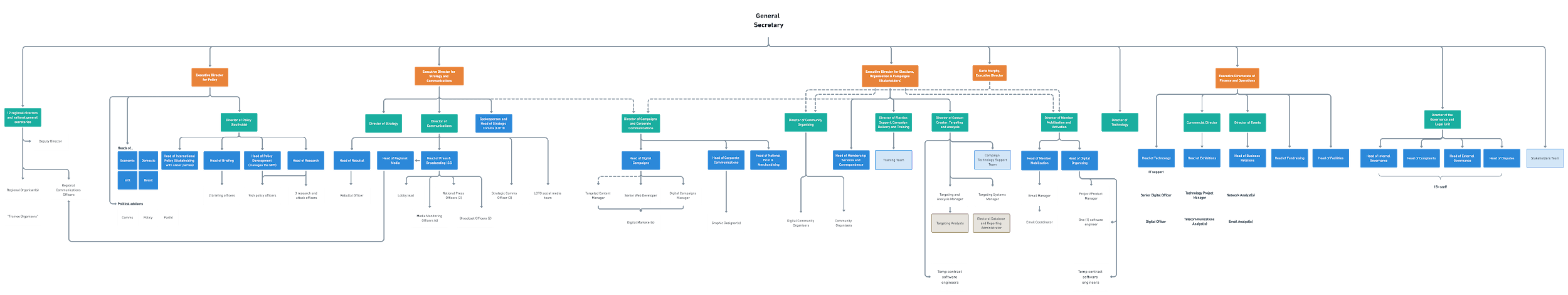

As we have shown above, the Social Media function of the party alone is split across five teams. Looking at the full organisational chart of the central Labour Party that we were able to piece together, we note that the structure generally is quite complex, with many verticals and shared reporting lines.

In the diagram below we have highlighted managerial job roles centred around the Southside and Newcastle offices, identifying at least 5 “executive directors”, at least 24 “directors”, at least 30 “heads” by title by comparison with a variable staff of 300-600, to illustrate a second point: the Labour Party seems quite top heavy.

Comments from staff seem to reflect this organisational structure:

-

Numerous managerial meetings, often contentious in nature

-

Trickled down orders that vary day to day

“For the whole duration I’ve been here, it’s been very rare to have someone trying to lay out ‘this is what we’re trying to achieve’ on a cross-organisational basis. It’s generally always been much more compartmentalised and then sort of run through the structure of daily meetings, with a whole lot of people in, that cascaded down to their team… some of that is just in terms of security or leaking and that kind of thing.”

— staffer who was hired more than three years ago“It was fucking chaos, no one knew what was going on day-to-day”

“Overall chaos of the grid”

“No one except for the most seniors had sight of the grid”

“Everything was ticking along but the broader strategy of what the campaign was doing just wasn’t there” — staff seconded to Southside for the campaigning period

“The Party as a whole is lost and confused, they are not sure what direction they are heading in which results in teams not working well together as everyone is out for themselves. There is no culture, no feeling of community as no one supports each other, which makes the London office feel very hostile and cold.” [10]

Bugs in the ecosystem

It has been well-noted that digital systems were unreliable and lacking certain features. We aim here to identify some trends and deeper issues.

Access to digital infrastructure

Possibly one of the most impactful and under-discussed examples of turf war syndrome is access granted to data and digital tools for decision making and campaigning.

From Southside staff down to constituency organisers, access to key tools like Contact Creator, Insight and Mosaic is regularly demanded, contested and denied.

-

We heard multiple constituencies were genuinely impacted by their ability of already-struggling campaigns to effectively deploy their few resources, refused access by staff teams after requesting it amidst conflicting information about which roles should be allowed access.

-

In other cases, requests for access to a tool to beat impending deadlines were frustrated by disputes and delays, resulting in missed opportunities.

-

In other cases, a limited number of key-holders meant that campaign teams developed bottlenecks when these people were unavailable or went on holiday, in some constituencies leaving no one able to plan doorknocking sessions during the general election.

-

Access to data and tools frequently causes disputes and interpersonal, and in some cases inter-organisational tensions

There needs to be a much more substantial review and clarification of how access is granted, to who, for what reasons, and BY who. Access to membership tools like MembersCenter, Organise and voter contact planning tools like Insight and Contact Creator were frustrated by the approval chain, local politics and grey-zone ambiguities in the rules and in law. “Data protection” is often the issue of refusal or delay.

There needs to be complete clarity about rights, access, provision, etc.

Confusion over GDPR

Quite aside from access and reliability, a basic problem encountered by people brave enough to plough ahead with phonebanking were told by regional: you must use Dialogue.

The rationale for this is that, as people have a right to know who is calling them and how their contact details were acquired, people should use the Labour Party’s infrastructure. However some constituencies used “burner” mobile phones after rationalising that, yes: you can say you were calling on behalf of the Labour Party.

GDPR particularly has been wielded as a weapon to regulate access, with contradictory reports about who can use and see what. A further knock-on has been ineffective use of data and tools to mobilise and organise members.

Legal clarity around the practicalities of GDPR and organising is urgently required.

“GDPR, or the party’s interpretation of it, has meant that the only way I can contact our members is through a national email system that doesn’t work effectively, adequately, or often enough… Over many years, administrative power has been removed from CLPs and gobbled up by the centre — this is bad enough: but when the centre has failed to create reliable systems, it’s worse.”

“Bore them into submission tactics” are required to get access to digital tools

— CLP officers

Usability of digital infrastructure

“My CLP has rarely, if EVER, used

Contact Creator, Insight or Promote.”

— CLP Secretary from the South East

A tech staffer noted that the “digital product as a whole” was not in great shape. It was deemed likely that constituencies where usage of digital tools was least prevalent typically were the kinds of constituencies that Labour suffered the most in. It is likely that poor access to and skill in using digital tooling, as with other campaign resources and techniques, affected the number of seats won by Labour in this election.

Ineffective use of tools has been highlighted in the past to the Digital Organising team but a lack of capacity has prevented much training or further development.

Gaps in the party’s digital ecosystem

What organising systems are desirable but infeasible, that could be enabled by digital technology? In lieu of a party-wide electoral strategy, door knocking and contact rates are implicitly the central focus of campaigning and to this end Contact Creator and its ecosystem are given the lion’s share of attention, but what follows a consideration of how to strategise year-round community action and party-building?

Door knocking and issue mapping

Most campaigns will track issues on the doorstep to prevent massive hiccups like not knowing anything about anyone — and yet the Labour Party was the only party this election not to have this nailed down.

Recording relations also identifies ‘path of least resistance’ canvassing options: actions members and supporters can take to influence friends, family, housemates and old colleagues that take advantage of pre-existing relationships.

Contact Creator has provisions for surveys and contact relations built in, but surveys are rarely used and relations are currently limited to housemates.

Every other major party in the UK has a system like this. The Conservatives had VoteSource, a bespoke tool.[11]

“Yes … we’ve covered that,” the activist ploughed on. “So how would you rank the parties on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is no chance you would vote for them, and 10 is you definitely would? How about the Conservative Party?” [12]

The Liberal Democrats have MiniVAN, the same tool that the Democrats use — an off the shelf legacy from Obama years, turned into a commercial company.[13] And the Brexit Party had Pericles which not only facilitated doorknocking, but on polling day also facilitated GOTV by highlighting not-yet-voted pledges on a map.[14]

In the US, tools like the BERN app have allowed activists to think through how they leverage their relationships via phone contact list analysis and “wallcharting”.

Related to this is the concept of casework management. Despite hundreds of MPs and thousands of councillors, no system exists to track case management for constituents. There are many such systems widely available and in use by charities, trade unions and other support organisations. At their best, they enable “big picture” views that can contribute to collective action and higher level campaigning. The Lib Dems have a comparable system for this.

A single view of voter contacts

With postal mail, door-knocking and phone-banking as well as social media all being aimed at voters as well as members, there is a gap in the ability to track all of this and to verify or measure the effect of contacts.

Members noted some occasions where voters would be frustrated by frequent repeat contacts and mail.

One issue is that, as most Labour Party canvassing still takes place with paper sheets where the data might not be entered for a few days, there is a significant risk of people being knocked multiple times in quick succession, especially if everyone follows the recommended model of where to knock next via the Insight tool. But this is not a problem that, for example, the Brexit Party will have as they don’t have any other canvassing infrastructure.

A canonical solution for GOTV

Turnout is not used by many constituencies, whilst various forms of excel spreadsheets abound to do the on-the-day organising. Campaign Lab’s GOTV tool is an alternative but has received limited usage. There must be a solution which can win us votes.

Activist mobilisation

“It seems to me that a key problem is that Organise is very Campaigning oriented, and has not been designed for the day to day activities that CLP secretaries perform as the major part of their role. This lack of understanding has given rise to many of the other issues… raised.”

— CLP secretary’s email to the central office

Labour used to use Nationbuilder on a £200,000 / year contract, which had pipelines, member management, voter contact management and numerous other features.[15] It’s replacement with Organise, an in-house platform built by a now-dissolved contract team, focuses on event management and email creation. Its flaws and reliability issues are well-documented and have in the past provoked CLP secretaries to collectively send letters to party management.

Areas of opportunity for the Organise platform, or an alternate contact management system include:

- Integrate with voter data (e.g. Contact Creator), so that voters can be identified as supporters and moved towards party activism.

- Training local party organisers in effective digital organising using existing digital tools and methodologies. Examples include wall-charting, community mapping and social media good practice.

Recommendations

In order to fill the above gaps there is a system-level series of changes that should be considered.

Organisational change

-

Any plan is better than no plan. The Labour Party must always have an objective that is shared amongst the team.

-

No more restricting the flow of information about basic operational matters like scheduling. No campaign is worth sacrificing team coordination for a spectacular reveal. Find a better strategy.

-

Re-role a whole wrung of managers to field organiser functions, to cut down on managers and increase the work that is done and the understanding on the ground about the work to be done.

Digital team change

-

Hire a substantial full-time permanent digital organizing team of 3x developers, 1x product designer, 1x user researcher to accompany the existing team lead, developer and product manager.

-

More than an ad-hoc digital strategy is required to facilitate the digital estate of a party of 500,000 members with an annual revenue of £60,000,000 and dozens of digital systems.

-

Digital space should be considered a core component of the party’s electoral strategy, as it is an increasingly influential space through which voter opinion evolves.

Programmes and initiatives

-

Make a medium-term commitment to disengage from Experian and end consumer surveillance as an electoral tool as a matter of principle. In order to do this, the Labour Party will have to commit to exploring and doubling down on alternative, less individualising and atomising forms of political organising that rely less on microtargeting — reliant on HQ — and more on relational organising — reliant on everyday members.

-

Mass programmes of digital tool training for members, officers, staff are required to leverage the existing tools at their disposal.

-

A streamlined and standardised system for granting access to critical digital tools for organising, visible to all party members, to ensure the right people have credentials for the right tools.

-

Legal clarity around the practicalities of GDPR and organising is urgently required, available to all party members.

-

A public roadmap of what is being built / fixed / improved in the next while. It is de rigueur for digital teams to have a public roadmap in commercial products.

-

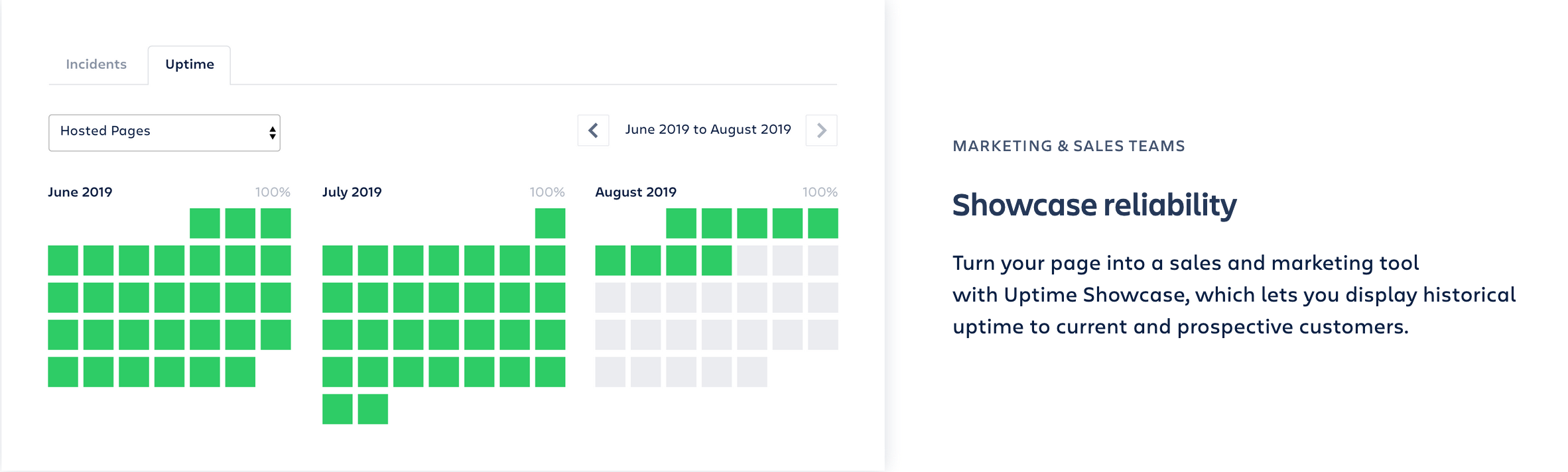

Digital tool uptime figures for all tools, with a central channel for status reports, to address the problem of uncertainty around digital tools’ availability.

Such systems also enable this to be tracked. The aim is not to apportion blame but to highlight to party leadership and the membership at large what the scale of the problem is, so that informed decision making can occur.

-

Develop a strategy for an open technology platform that third party developers and activists can use to facilitate their own organising through the party, and contribute back to the system through hackathons and volunteer management.

-

Existing digital tools need to be vetted for their mobile-responsiveness and availability when offline or out of signal, for example in rural areas or high-rise tower blocks. More generally, accessibility needs to be upheld as a core principle in the Labour Party staff development community and facilitated by management through funding.

-

See https://www.codersforlabour.com/ and https://github.com/coders-for-labour

-

See http://www.getoutthevote.uk/ and https://github.com/bobwhitelock/gotv-dashboard

-

https://github.com/celestial-winter/vics

-

Elizabeth Chamberlain et al., ‘The Road Ahead 2020: A Review of the Sector’s Operating Environment’ (NCVO, 27 January 2020), https://publications.ncvo.org.uk/road-ahead-2020/.

-

Julie Goran, Laura LaBerge, and Ramesh Srinivasan, ‘Culture for a Digital Age’, McKinsey Quarterly, July 2017, 10.

-

‘The Five Trademarks of Agile Organizations | McKinsey’, accessed 16 June 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-five-trademarks-of-agile-organizations.

-

Anonymous comment by an ex-staffer from the employer review website Glassdoor: https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Reviews/Employee-Review-Labour-Party-RVW24857581.htm

-

https://apps.apple.com/gb/app/votesource-canvasser/id1448349231

-

‘Conservative Canvasser Fails to Recognise Lynton Crosby’, accessed 5 March 2020, https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2019/12/conservative-canvasser-fails-recognise-lynton-crosby.

-

Gavin Haynes, ‘The Technology That Could Help the Brexit Party Win an Election’, Vice (blog), 12 September 2019, https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/vb574x/brexit-party-pericles-election-app.

-

https://www.linkedin.com/in/joshua-graham-140a43a6