labour-together-ge2019-review

In lieu of strategy: ground operations and organisational structure

Common Knowledge’s submission to the Labour Together’s report on Labour in the 2019 General Election.

The other is System updates required: ground operations and digital technology.

Contents

The challenge of objectively evaluating the party

Headquarters strategy and communications

2019

The challenge of an active membership

Experiments in community organising

Experimentation and party culture

Recommendations: community, membership and constituency

Given the situation the party finds itself in, the scale of the defeat and challenge ahead, this report aims to (a) give clarity and creative assessment to the complaint that Labour’s digital technologies are a disappointment and (b) to add clarity to the puzzle of community organising as a party function. What can realistically be gained from the discussion of “getting back into the community?”

The rest of this report will elaborate on the primary themes of digital technology and community organising by highlighting and exploring various challenges of running an election campaign with the party machine as it was available in the Autumn of 2019.

Key insights

- This report’s top line assessment of the Labour Party’s 2019 general election campaign is that, amidst generalised uncertainty over political communications and strategy, the party did not have a practical party-wide plan to win the election, leaving party staff and members to conduct a conventional and fairly mediocre ground and air operation. This was described to us by various phrases amounting to “business as usual” and a redo of the 2017 campaign, a campaign itself that largely worked in the same manner as 2015. Tellingly, whilst the campaign seems to have improved in terms of a few operational metrics since 2017, it clearly failed in many practical regards (not to mention political) and by some notable measures, likely degraded.

-

Member activity to be stoked. Fundamental voter ID operations were inhibited by a lack of year-round membership activism, with officers and staff wishing for more involvement whilst both recent and long-term members are uncertain about how to get involved and in many cases are passively dissuaded by their experiences with the local constituency and general party apparatus.

-

Constituency capability to be developed. The short campaign’s substantial increase in member activity did not generally mirror an improvement in the technical ability of campaigns to run an operation. The prevailing themes were consistent uncertainty around basic rules, regulations, procedure, techniques, operations and plans, reporting lines and structures of the party. Many members, officers and staff were led to feel variously unconfident, unskilled, unprepared and poorly resourced to run even a business as usual campaign.

-

Digital access to be unlocked. In particular, substantial evidence points to widespread irregularities in provision of access to data and digital tools which enable a constituency to operate even a basic campaign, with reports of explicit refusals, communication issues, uncertainty and delays sufficient enough to negatively affect numerous campaigns’ basic voter contact activities.

-

Technical debts to be paid. Furthermore, although members, officers and some staff share a view that the party’s digital tools are difficult to use if not basically unreliable, there is only one permanent software developer and no clear strategy or investment for maintaining and developing digital tools which facilitate constituency organising.The Voter ID-enabling suite of tools—Contact Creator, Insight and Mosaic—which are themselves increasingly in need of iteration are managed separately.

-

Experimentation to replace contention. Attitudes towards the Community Organising Unit (COU) allowed lop-sided, informal scrutiny over team performance which was not applied equally to all teams. If leant into and practiced more widely under the auspices of shared goals could form the basis of a vibrant and innovative party campaigning culture. At the moment it leads to unproductive interpersonal and inter organisational tensions.

-

Conventions to be transparently evaluated. We agree with the general conclusion that, in the short campaign alone, a more effective ground operation would not be able to bridge the gulf of possibility between the party and the electorate. In fact, we are pleasantly surprised that so little preparation and campaigning has resulted in so many seats held. The party should do more to actively work outside of the short campaign. As has been generally commented on and substantiated by Lord Ashcroft’s post-election voter analysis[1], perceptions of distant Labour councillors spoke to the perceived attitude of Labour in government and weakened the party’s trust in the eyes of the public

The challenge of objectively evaluating the party

This research project collected new evidence from a qualitative review of 10,000 survey responses, a noting of common themes throughout the dataset that speak to well-established and relevant party issues. The research then conducted follow-on anonymous research interviews with people with direct experience and understanding about relevant functions of the party in terms of their self-organisation, coordination with the rest of the party and longer term perspective on the party’s operations.

In producing this report, we note our efforts have been hindered by staff and to a lesser extent members being reluctant to speak even under the condition of anonymity. This has been exacerbated by the direct briefing by Labour Party senior managers not to engage with the research effort and pointed complaints to the commission for seeking comment. Whilst we recognise that internal investigations may well be occurring, it is unclear how much of this information will ultimately come to light, considering our experience in conducting this investigation. Indeed, we believe party transparency to be a productive area of discussion for the themes at hand. Accessible data with which to assess our party’s operations has arrived mainly through leaks to the press and in some cases through anonymous commentary to the commission, but this speaks to the opaqueness of a political party and contributes to our challenge in the Labour movement of mounting a constructive critique of the electoral machine and the leadership of the party that is, ultimately, one of the most central vehicles of progressive politics in the United Kingdom. As this report will explore, a lack of transparency has generally allowed a culture of “stay in your lane” and “are you authorised to see this?” to prevail. The reaction of some Labour party staff and members to conducting this report sadly reflects a culture of secrecy and hostility towards even good faith attempts to recommend changes that is ultimately counter-productive. We thank the people who did contribute for their time.

This report also takes into account an appraisal of Labour Party constituency membership experiences, community organising and digital technology by a previous round of research conducted for a not-for-profit project in October 2018, which interviewed 20 London-based activists and organisers with various levels of party experience. It also draws on Common Knowledge’s direct experience of work in the Momentum offices developing the MyCampaignMap and MyPollingDay digital tools, in occasional coordination with Labour Party staff.

The intention is to provide a good-faith analysis of practical and organisational matters, from the perspective of researcher practitioners of digital technology and political organising including in a UK and international political and third sector context. In our work here we have attempted to perform a “no-blame” analysis, looking at systems, limitations and possibilities, rather than counter-productively focusing on persons and blame, a technique common in the software engineering industry.

Headquarters strategy and communications

As the commission heard directly, fundamental disagreements about voter coalitions and political strategy played out between multiple levels of the Labour Party’s political representative and staff units. From 2015 this was most fundamentally along factional and pseudo-factional lines and from 2016 was overlaid by the dividing issue of EU membership and following the Brexit vote on the handling of the referendum result.

These congealed divisions within party headquarters hindered the development of a coherent and shared strategy. Such a strategy might have been developed in detail and practiced throughout the different teams and functions and structures of the party. Instead the commission heard from staff about a generalised, almost ‘cultural’ norm of contentious and unconstructive meetings in Labour Party HQ (generally referred to as Southside) which have at times deferred more practical and creative decision-making.

Although we know that many of the campaign dysfunctions noted in 2019 were preexistent in previous election campaigns, a strategic approach to communications may have allowed the Labour Party to sidestep the effects of some of these internal contentions in the 2017 election. Following the change in party leadership in 2015, a new Executive Directorate of Strategy and Communications was created out of previously separate teams and roles, mirroring the new function of Strategic Communications in the Leader of the Opposition’s Office (LOTO). It was able to make a simple pitch to voters that they would respect the EU referendum outcome and then roll through a daily grid of perceived ‘radical’ policies in which the manifesto debuted, with a frantic activist-led mobilisation strategy that involved, for outrider organisations like Momentum, emphasising marginal seats of any kind.

2019

By comparison in 2019, the ability of the political leadership to coherently speak about Brexit was felt to have been lost, as political contentions accumulated and the ability of the party’s leadership to decide on a consistent and substantial approach to strategic communications around the subject declined.

Asked what they understood the 2019 election strategy to be, within which their work fitted into, party staff and members generally responded with uncertainty, often falling back to their job description, before noting that in Southside especially these are frequently not congruent with day to day responsibilities. In practical terms, this election was felt to be simultaneously “business as usual” as well as lacking in some obvious basics.

“This was a bog standard election”

— Regional staffer

Central party staff reported not knowing in advance the arc of the campaign, upcoming announcements even a few days away, or how to contribute towards the election beyond their team’s own day-to-day technical tasks and occasional calls for collaboration from pre-warned staff.

The central party’s communications grid was adhered to, which a party source noted bore a strong resemblance to 2017’s, in tandem with a secretive approach intended to prevent leaks. There is a difference between protecting aspects of a campaign from operational risks associated with opponents awareness and doing this to an extent where it hampers one’s own effort. It should be noted the Tories “red wall” strategy was extensively briefed to the press both prior and throughout the campaign. Anecdotally, Dominic Cummings explicitly told senior Labour advisors of their strategic gambit to goad them into an election! It is not important that a strategy is secret for it to be effective.

In lieu of a more substantial strategy which articulated precisely what election gains could be achieved and how different parts of the party would concretely work together, individual units progressed through their own day to day campaign calendars in the hope that the parallel efforts of everyone would have an aggregate effect by virtue of the fact they were nominally part of the same campaign.

The challenge of an active membership

A substantial challenge for the party in this election was to mobilise volunteers to canvas the electorate at their doors, in the cold and early darkness of late Autumn. At least one critical internal party report, leaked to the Guardian, has already broken down the dysfunctions of the Labour Party’s Voter ID operation, noting a deficit of skill, resources and activity amongst constituencies.[2] The commission has accumulated a bulk of evidence of the same, suggesting there should be much more serious concern for the many local parties that cannot rely on their membership to conduct year-round voter ID to the extent that facilitates an efficient, let alone effective, election campaign. There is plainly consensus that year-round member activity is low, that the responsibility of constituency organising is often handled by frequently “more experienced” members and that this is affecting year-round contact rates.

How was this often dysfunctional campaign allowed to happen? The evidence suggests that this was not a buck in the trend; the “business as usual” structures of the Labour Party relied on in 2019 was compositionally very similar to 2017 and likely even earlier election campaigns, despite changes in paper membership and light team restructuring. Yet despite the 2015-2019 party leadership’s vocal support for “member-led”, “grassroots” party activity, practical consensus that improvements are needed. Apart from the existence of a Membership Mobilisation and Activation Team in Southside, we were unable to identify a party-wide membership strategy in operation at constituency, regional and national level to rectify this situation and the implications for constituency campaigns are bad.

Membership as a process

“We’ve generally seen the Membership Officer role as an administrative one, but I guess we should have a strategy”

— Executive committee member in the South East

Community organiser Arnie Graf was hired by Ed Miliband to write a 2011 report on the dysfunctions of the Labour Party and identified some fundamental issues which at this point are uncontroversial but worth restating:[3]

-

“A bureaucratic rather than a relational party culture” in local constituencies which severely limits the potential of what membership can mean.

-

Centralisation of decision making power away from members, and towards London-based senior leaders and staff.

-

A closed culture, suspicious of outsiders and inaccessible to newcomers.

-

A general consensus that meetings, which comprise the bulk of regular Labour Party business, are dull rather than first and foremost emotionally inspiring events.

Our investigation of the party in 2019 found little contrast. Graf’s suggestions in 2011 included:

-

A trial of open primaries, where parliamentary prospective candidates are selected by the electorate at large rather than by the local party membership or national party leadership.

-

A supporters network membership tier, sold to sympathetic voters as a lesser commitment than membership on a ladder to Labour Party engagement.

-

Collective party membership for community groups, in the same fashion as trade union and socialist society affiliation.

Recommendations in this vein seek to bridge people through stages of lower to higher commitment, with an emphasis on increasingly practical and collective social engagement within the “extended Labour Party universe” based on preexisting relationships with individuals and groups in the area. This is a standard systematic approaches shared by political organising and other functions like sales. Similar conceptual models include “pipelines”, “funnels” and “wall charts” more frequently found in political and trade union organising.

Voter → Supporter → New Member → Engaged Member → Organising Member

With a conceptual model in place, organisers and organisations can ensure that bridges exist to move people along to higher commitment, and address barriers to movement. A process framework like this also makes it simple to measure and evaluate the membership system: administration becomes a case of investigation, experimentation and improvement, rather than of static management.

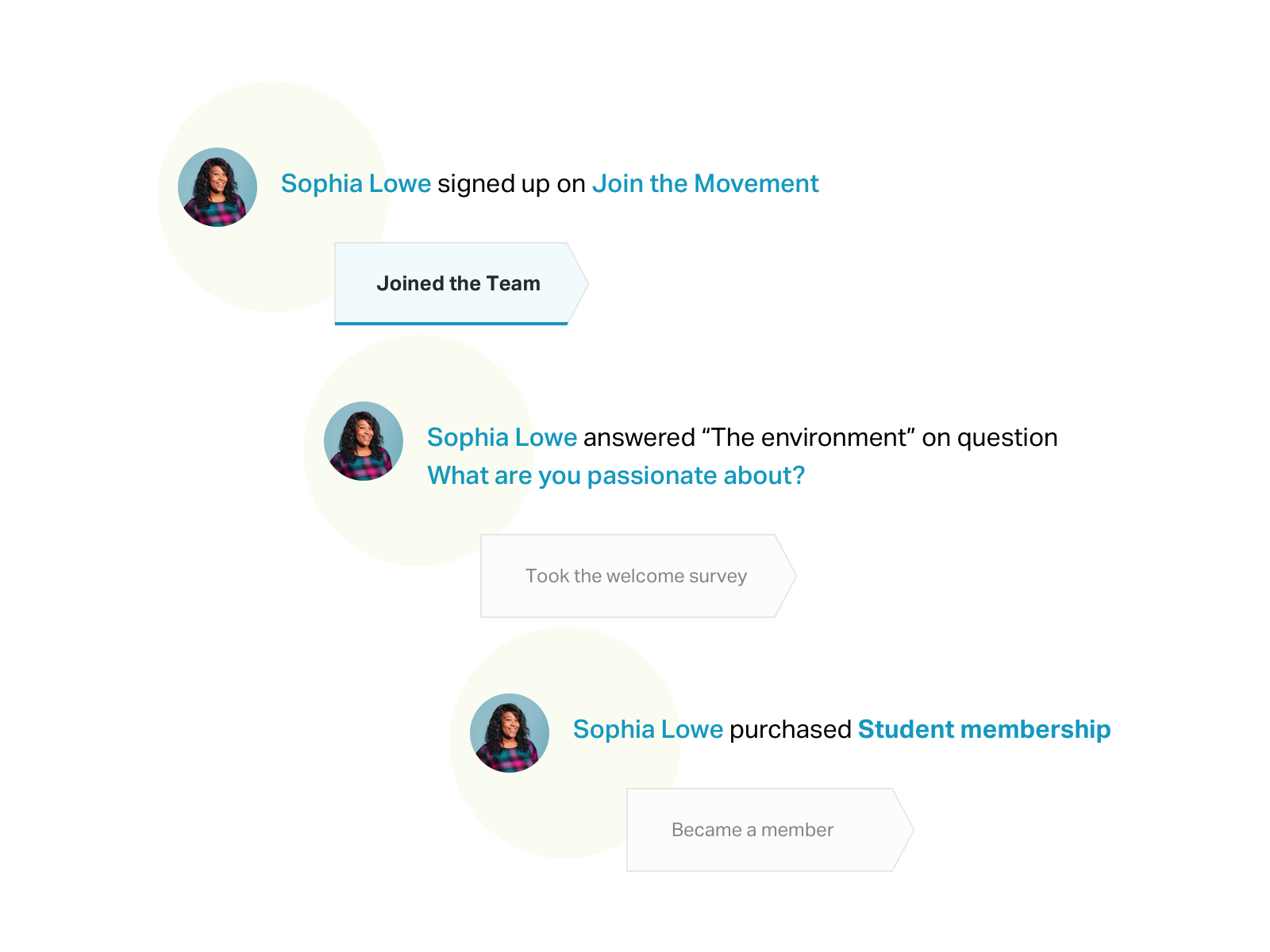

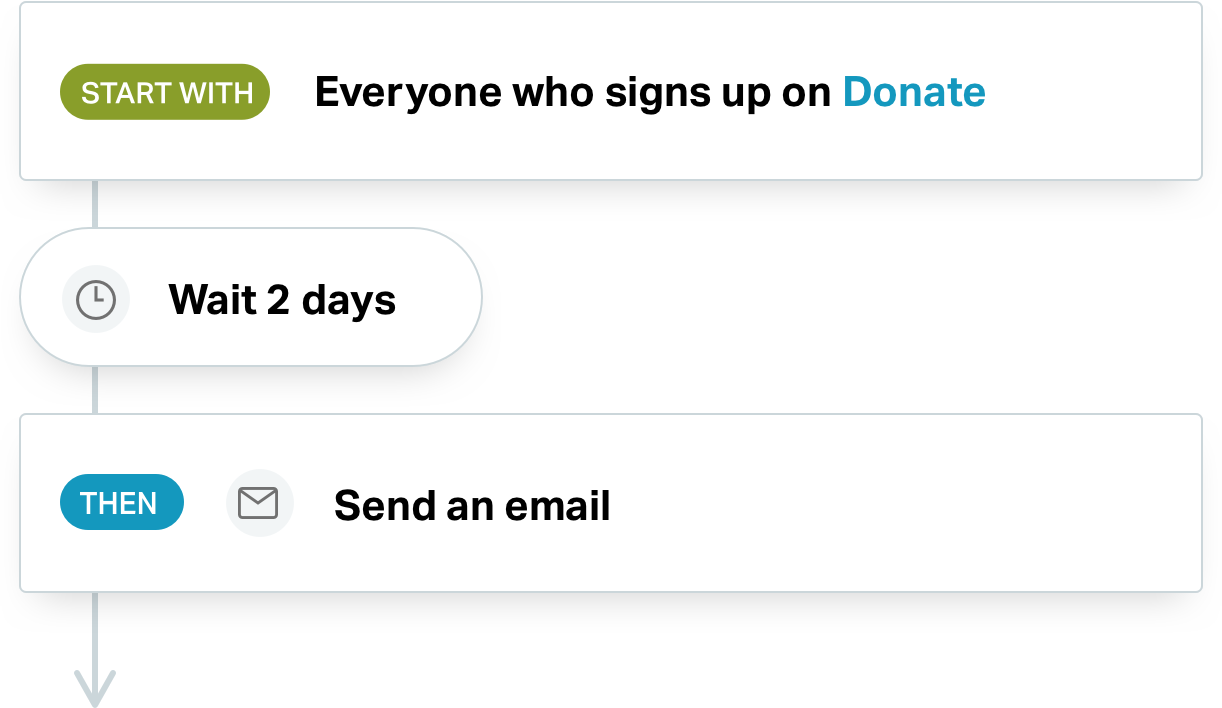

Digital organising platforms like Action Network and Nation Builder, which the Labour Party previously paid around £200,000 per year for until its replacement by the bespoke Organise system, have long encoded pipeline systems for individuals that can concretise this approach.

###

Much like a constituency can measure and optimise its canvassing and direct mail schedule, doorstep techniques and messaging to make the most of the Voter ID system, the required inputs for this system — members and good local knowledge — can also be systematised, measured and optimised.

Disappointingly, we routinely heard experiences of members first receiving a Labour Party email only many months or even years after joining, also variously receiving postal materials, a symptom of an inconsistent approach to active membership for basic Voter ID operations.

“CLP politics needs to move beyond just passing motions. CLPs are too inward focused, meetings are often hostile to new members and are often very procedural and boring. (I’ve been a member for 6 years and still only go relatively infrequently and I’m a labour obsessive that follows every turn in the media and canvassed countless hours in the campaign).”

— Canvasser from Walthamstow CLP

The theme of constituency accessibility comes across strongly in feedback to the commission.

Experiments in community organising

In the aftermath of the 2019 election what has been added on to the broad consensus about party dysfunctions is the discussion that, in some way, the party must “get back into our communities.”[4] Yet this was also a stream of discussion in the 2010 party leadership race, where the Movement For Change initiative was developed and later operationalised under Graf’s supervision into a mass community organising programme including 200 paid organisers and 1,000 more volunteers trained to work in marginal seats.

The model was comparable to that employed by Labour Party councillors especially in the middle of the 20th Century, when trade unions and labour party were considerably more intertwined on a day to day grassroots level: councillors were sometimes described as “neighbourhood shop stewards” and one interviewee we spoke to from Manchester recalled that councillors were expected to diarise their contacts and casework with residents and submit to scrutiny and disciplining about how engaged in the community they were. In 2019, perceptions of Labour councillors were particularly dim:

“They take our votes for granted and think we were born yesterday.”

More broadly, “I don’t think they get out and listen to people like they used to. They used to be part of the local community, but they became complacent. They thought ‘whatever we do we’re going to get the votes off the local people, especially in the North,’ but it didn’t work like that;”

“The council has been Labour all my life and they are shocking. Fly tipping is awful;”

“Stoke has always been Labour but it hasn’t done us any favours. If you walk round, some of it is quite scary. It was voted the 9th worst place to live;”

“Bridgend has grown exponentially but how many new hospitals and GPs have we got? You’d think they’d take these problems back to Westminster. There are more and more people but there is no infrastructure, no plans, nothing;”…

“In Conservative-led councils, the roads are better, the schools are better.”[5]

Perhaps the most identifiable attempts to continue this experiment within the party since Graf has been the Community Organising Unit (COU), active since 2017, seemingly taking on many of the accumulated suggestions. Following the same Alinskyite model,[6] each organiser is assigned to one or more target marginal seats and is tasked with mapping their communities, identifying and building relationships with community leaders. Community campaigns are developed through these collaborations which can demonstrate the practical outcomes of the local Labour Party, building affinity to the party and possibly on-ramping new members. This can involve trainings in community organising and the like.

Where the COU has gone further is in its experimentation with community-driven policy formulation, notably contributing to the priorities and framing of the Green Industrial Revolution and Free Internet Broadband policies in collaboration with Shadow Cabinet staff. Workshops and “barnstorm” town-hall style meetings unearth collective opinions and needs in a similar vein to focus grouping, only in this case conducted by party staff.

After locally identifying policy and framing opportunities, this model seems to have broken down in the transmission through to the national party and less clear methods for policy development and communication to the public. Much of the value of this model is in the narrative of local communities designing their own futures. In lieu of a party-wide strategy there seems to be no strong mechanism for effectively enabling these initiatives, without substantial political and personal sponsorship to defend it from dilution and hollowing out through the prevailing policy development system.

Experimentation and party culture

The COU has been a contentious experiment in alternative organising. It emerged in a more explicitly factional and politically antagonistic period amidst the EU referendum result than did Graf’s initiatives. While there are differences between the two in terms of approach and theories of change, it is highly likely that similar party dynamics affected both attempts to build a community organising function within Labour.

Efforts in 2010-15 to reorient the party towards membership- and community-centric organising, predominantly in target marginals, could not prevent 2015 general election defeat. Graf noted that the organisers he had advised to recruit were conducting, on average, only 0 to 3 meetings with community members per week. Instead, administrative duties like data entry, membership dispute and compliance investigations swamped their schedules and there was a preference to use available time to conduct basic Voter ID.[7]

“How can the Party grow if the organisers are meeting so few new people? How can they develop local issue campaigns if they are not meeting the informal leadership that exists in every community in the country?”

Presumably, hired organisers were conducting Voter ID because of a lack of organic local membership which could be relied on to maintain acceptable contact rates, but then this entirely sidelined the objective of the community organising strategy: party growth which can appreciate people as members of their community before their party. A generally passive resistance to change in favour of business as usual still seems self-evident in much of the party. COU interviewees summarised intra-organisational challenges as a “cultural” problem, “not even just from the top.” They frequently referred to a “resistance to change” and observed a prevailing feeling amongst those who had “always done things a certain way,” something also noted by Graf.

A prevailing measure of performance will inevitably trickle down into the decisions around resource allocation, team coordination, preparations and improvements. Our assessment is that “contact rates” as the prevailing measure of party performance has likely prevailed over and against any particular political strategy in at least the last four election campaigns, and this prevailing view has repercussions.

-

Despite an explicit operating model, the COU has suffered from a consistent illegibility problem, for instance being frequently confused with the Training Team.

-

One effect was a perceived need to frequently justify the COU’s budget and approach through voluntary reports, often from the perspective of ‘contact rates’. There was a feeling of disproportionate pressure and scrutiny on individuals, resulting in some welfare issues. But do other teams and units regularly report on their outputs and outcomes? What would an analysis of proportionate input/output/outcome of different teams reveal about the relative efficacy? Would we deem the general scepticism towards the COU to be justified? This has not been possible to conduct without breakdowns of budget and substantial data, but a more consistent and universal approach to the scrutiny experienced by the COU could positively orient party culture in the direction of action, rather than turf.

-

Ironically, in attempting to support election-time canvassing through persuasive conversation training, there was a general puzzlement as to why the COU was not instead doing community organising and in some cases the critique was levelled at the unit about why precious canvassing time was being diverted into training.

-

An organisational focus on Voter ID has had long-term effects on infrastructure. The commission noted generally positive feedback about the tools Contact Creator, Insight and Mosaic 6 which critically support the Voter ID-oriented party operations. By comparison, tools that supported activities other than straightforward doorknocking including Organise, Connects, Promote, Dialogue and Doorstep were much less reliably available, useful or approved of by members, to the detriment of more general campaign and party operations.

Graf’s recommendations in the aftermath of the 2015 general election in comparison to the 2011 recommendations in their focus on cultural change rather than novel ideas. Recommended advice included more frequent meetings with regional directors and organisers in the field and a dissolution of the distinction between the leadership, national and regional staff.[8] Specifically for the Movement For Change programme of organisers, the advice was to commit substantially more time to the relational organising and additionally conduct trainings in basic public skills and organising techniques to increase and reproduce these activities; explicit measurables which COU organisers themselves track such as 15 one-to-one meetings per week with community leaders aside from trainings and other measurable activities.

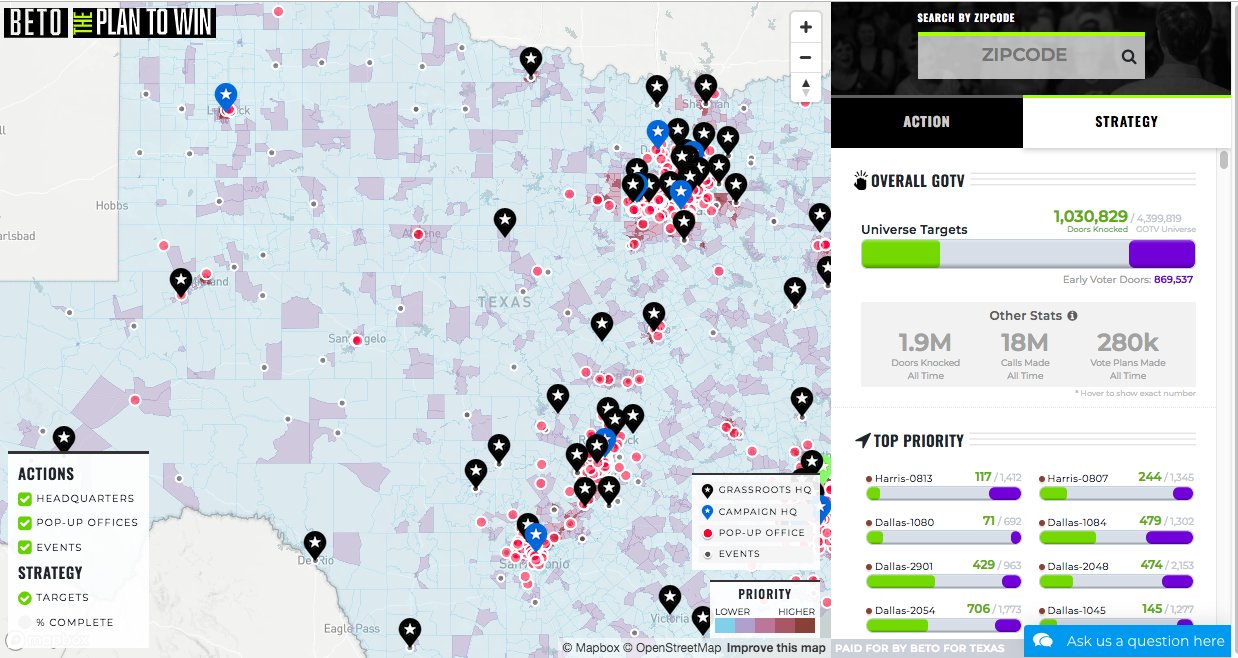

KPIs, objectives and key results, and other measures of fundamental outcomes are de rigueur for collective organisation in other political campaigns, governmental departments, charitable organisations and commercial firms. The Beto O’Rourke campaign of 2018 went so far as to publicly display all contact rates data on a website to enable member self-organisation.

We have a series of recommendations for further discussion, development and inclusion in the commission’s final publication, based on the above analysis.

Recommendations: community, membership and constituency

To encourage greater accessibility and transparency between party and community.

-

All general meetings to be made available to the public and advertised as forums to discuss local issues.

-

Encourage and fund delegations of members to meet with members in neighbouring branches and constituencies and regions for educational visits and solidarity-building.

-

Press ahead with supporter network and community group memberships.

-

Increase the ratio of regional organisers to central office staff supported by a Constituency Development Budget.

-

Roll-out of political organising weekend and weeknight courses in target seats, accessible to any member and aimed at different

-

Start measuring different aspects of election readiness, and make all data for all constituencies should be publicly accessible via an analytics web page. This will ensure transparency and pressure to face up to the facts.

Measurements might include:

-

“Residents per active monthly member” ratio — check whether members have shown up each month with a tick box. Can be self-reported and/or noted by constituency organisers/officers.

-

Three month rolling new members

-

Three month rolling lapsed members

-

Digital access rate (%) of CLP and BLP officers with self-reported correct access to core tools like Organise, Contact Creator, Insight, Promote, Connects.

-

Measurements of “contact rates” should be more nuanced if they are to be used as a north star for party organising. At present they privilege aggregate “official” party activity directed at individualised voters, rather than everyday interactions between party members and their fellow community neighbours.

-

Three month rolling contact rate

-

Average age of party preference report

-

Monthly rolling weekly resident contacts per councillor / organiser / caseworker

-

-

Diarised casework and resident contact activities by elected officials such as councillors, MPs

-

A national listening campaign which also builds visibility, local party activity, leading to a handful of national campaigns per year, that can link the air war and local organising. E.g. renter rights, £10 min wage. This would simplify production of generic assets and build visibility/material results/organic links between local party members and community

-

Political and communication strategy and production should be much more focused on the story of “us, not me” community relationships, consensus-building, policy-design and organising by communities themselves, rather than the menu of output policies.

-

‘Diagnosis of Defeat: Labour’s Turn to Smell the Coffee’ (Lord Ashcroft Polls, 10 February 2020), 17, https://lordashcroftpolls.com/2020/02/diagnosis-of-defeat-labours-turn-to-smell-the-coffee/.

-

Kate Proctor, ‘Labour’s Canvassing Strategy Had “Major Deficiencies”, Leaked Report Says’, The Guardian, 7 February 2020, sec. Politics, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/feb/07/labours-canvassing-strategy-had-major-deficiencies-leaked-report-says.

-

Rowenna Davis, ‘Arnie Graf: The Man Ed Miliband Asked to Rebuild Labour’, The Guardian, 21 November 2012, sec. Politics, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/nov/21/arnie-graf-labour-party-miliband.

-

‘Labour’s Path Back to Power Will Be through on-the-Ground Activism | Lisa Nandy’, the Guardian, 3 January 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jan/03/labour-power-activism-leader; ‘In Defence of Community Organising’, accessed 16 June 2020, https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/02/in-defence-of-community-organising; Chaminda Jayanetti, ‘The Problem with Labour’s “Community Organising” Pitch? It Has No Idea How to Organise a Community’, accessed 16 June 2020, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/community-organising-labour-party-chaminda-jayanetti; ‘Labour’s Complacency Lost It Northern Seats — the Tories Must Change to Keep Them’, accessed 16 June 2020, https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2019/12/labour-s-complacency-lost-it-northern-seats-tories-must-change-keep-them; ‘Organising Is in Our DNA - Now We Need It More than Ever’, LabourList, 19 January 2020, https://labourlist.org/2020/01/organising-is-in-our-dna-now-we-need-it-more-than-ever/; John Harris, ‘A Labour Revival Must Tap into the Energy for Change on the Ground | John Harris’, The Guardian, 15 December 2019, sec. Opinion, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/15/labour-revival-change-community-activists-plymouth.

-

‘Diagnosis of Defeat’, 17.

-

Saul David Alinsky, Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals, Vintage Books ed (New York: Vintage Books, 1989).

-

‘Labour’s Failure Had Little to Do with Organisers in the Field’, LabourList, 4 August 2015, https://labourlist.org/2015/08/labours-failure-had-little-to-do-with-organisers-in-the-field/.

-

‘Labour’s Failure Had Little to Do with Organisers in the Field’.